Report from Iraq[1]

By Michael W. Albin

This presentation is a follow-up to the paper presented at the 75th Jubilee of the DC-SLA. It’s divided into two parts. The first is a good news story about preservation and digitization of manuscripts from my trip last month to Iraq’s Kurdistan.

The second portion is a comment on the continued confused state of preservation and conservation in the region. Sadly, this is not such a good news story.

I’ll start with very good news indeed about Iraq, and in specific by describing a heroic effort in 2014/2015 after the ISIS blitz against Mosul in Iraq and its occupation of the churches and monasteries in the city and environs. Fr. Najeeb Michael went from church to church to load the precious contents of their libraries into cars and carry the centuries’ old treasures through enemy lines to safety in Erbil. Under cover of darkness, he spirited some 800 manuscripts out of Islamic State territory. Many of the treasured works of art are beautifully illustrated manuscripts written in the finest Syriac script, and exquisitely bound in leather. The manuscripts are now under lock and key in secret locations in and around the capital city of Iraqi Kurdistan, and protected against the elements: heat, humidity, dust, and human predation.

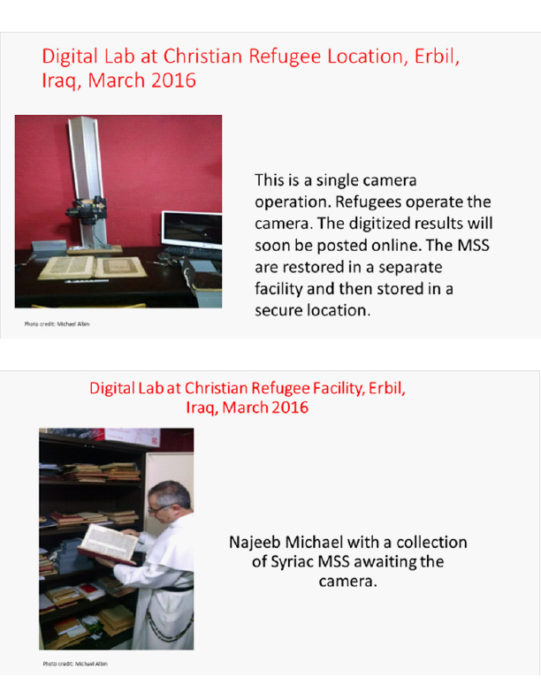

Fr. Najeeb, whom I visited on March 17 along with Fr. Columba Stewart, the well-known director of the Hill Museum and Manuscript Library at St. John’s University in Collegeville, MN said that currently there are 3000 codices out of harm’s way. He releases only those that need immediate digitizing and treatment for damage or rebinding. These operations are carried out at two locations in facilities shown in these illustrations.

Restoration technician displays shipment of tools and supplies from Italy. Photo Michael Albin

I might point out that Fr. Najeeb has been occupied with preservation of Iraq’s Christian and Yazidi manuscript heritage since the 1990’s. Always strapped for funds and concerned about hostile attacks by his neighbors, he was able to set up operations in the town of Qaraqosh, not far from occupied Mosul. Today, that unhappy town is in a no-go zone and was off-limits to me on my trip north.

You can learn more about Fr. Najeeb and his operations without actually going to Kurdistan yourself by visiting the Hill Museum website or the Centre numerique des manuscrits orientaux, a branch of the Dominican house in Paris.

Taking the liberty of quoting myself, I’d like to refer to a comment I made during a VOA interview on April 18. “The manuscripts rescued by Fr. Najeeb Michael are as important for the history of Iraq’s culture as any museum object or archaeological site.”[2]

“The manuscripts rescued by Fr. Najeeb Michael are as important for the history of Iraq’s culture as any museum object or archaeological site.

I had intended to pay a visit to the Iraqi Institute for the Conservation of Antiquities and Heritage, a most important international enterprise located in Erbil. Unfortunately it was closed for the week-long Nowruz observance. But by happy coincidence I ran into book conservator Irene Zanella, who’s been working there on and off for several years. Those who recall my last talk on the subject remember that I was critical of this institute in that its operations concentrated on museum objects rather than books. That problem has now been fixed, thanks to Ms. Zanella. She told me that conservation work and training is alive and well at the Institute with funding and support from the Italian government. The Italian government is also assisting in the training of conservation technicians from the refugee community working with Fr. Najeeb. As of a couple of years ago she was conducting classes for sixteen professional conservators and by this time she will have trained many more.

I’d like now to turn attention to the second part of this brief talk and to mention some less encouraging findings from the trip. In the main, these remarks are the result of long conversations with Dr. Saad Eskander who was, until recently, national librarian of Iraq. Like Fr. Najeeb Michael, Dr. Iskander has demonstrated heroism and administrative genius in preserving the collections of the Iraqi National Library and Archives in Baghdad and establishing a digitization project that Dr. Van Odenauren can tell us a great deal more about from the perspective of the World Digital Library.

Now in retirement as a private citizen, he resides in Sulaymaniyah a Kurdish city, and remains a well-informed observer of cultural preservation activities on both sides of the country’s north/south divide. Anyone who knows how frank, not to say blunt of speech he is will guess that I got an earful about the way the two governments are handling the bibliographic and archival history of the country. His is a stinging critique of bureaucratic red tape, sloth, and corruption in Baghdad and Erbil. By contrast, he had most complementary things to say about the treatment of such cultural treasures in the Shiite holy city in the south, Najaf, which he held up as a model for preservation attention.[3]

He also recognizes that the country generally suffers from an economic crisis never before seen in the modern history of the country, or at least since the early 1950s, when oil revenues were devoted to development projects, including cultural heritage. Under such circumstances there is little that governments can do to raise the priority of cultural preservation and restoration.

What he told me, in summary, is that the rescue, preservation, restoration, and digitization of manuscripts and other rare books, newspapers, periodicals, as well as state archives has never proceeded very well in Kurdistan, even in times of petroleum prosperity. The Kurdish region is an example of neglect, indifference, and the downright ignorance of officialdom of the historical importance of the materials that lie exposed to the elements in damp, dusty storerooms. An example Dr. Eskander used was of government archives in Erbil, the life history, as it were, of the modern Kurdish provinces and the foundation of what Kurds hope will be their independent state. Because of the Nowruz holiday I wasn’t able to call on the Barzani Library at the Barzani National Memorial in Erbil. This library is said to devote its energies to preserving newspapers and periodicals. Unfortunately, it has no Web presence.

In conclusion I want to be clear that I don’t mean merely to criticize the authorities in these remarks, but also to highlight that there is much work to do above and beyond keeping cultural treasures out of the hands of ISIS.

And really in conclusion, I’d like to emphasize, as I did at our session last October that to my mind the single most important source of trustworthy information on destruction is the weekly reporting of the American Schools of Oriental Research. http://www.asor-syrianheritage.org/weekly-reports/

There are other organizations, dozens of them world-wide, currently assisting in the effort. In the forefront is the Antiquities Coalition which takes the lead in keeping the cause constantly before the media and policy makers. https://theantiquitiescoalition.org/

MWA 4-23-16

[1] Paper read at the panel entitled “World Cultural Heritage Sites at Risk: Lecture II. Preservation Efforts in Libraries and Archives in the Middle East,” held in Washington, D.C. April 21, 2016 and cosponsored by the Sultan Qaboos Cultural Center and the DC Chapter of the Special Libraries Assn. Other panelists were Jesse Lambertson of the SQCC, John Van Odenaren of the Library of Congress, and Peter Herdrich of the Antiquities Coalition.

[2] http://www.voanews.com/content/iraqi-priest-rescues-ancient-manuscripts-from-islamic-state-destruction/3290975.html

[3] In a private communication of April 22, 2016, Dr. Eskander had this to say about archives and MSS: “Erbil neglected mostly documentary heritage, whereas the ministry of culture in Baghdad neglected the collections of the National Manuscripts Centre in such a way that it resulted in the destruction of thousands of them. These collections were kept in iron made boxes for years and never reserved any restoration. Recently the Italian government decided to donate a modern restoration laboratory.”