Reliefs from Ashurnasirpal II’s Nimrud palace, fixed to the walls of a Scottish mansion, have been removed, stripped and sold abroad

MARTIN BAILEY29th January 2019 11:03 GMT

The Assyrian reliefs were removed and sold by Newbattle Abbey College and Michael Ancram for £8m, although they had been in the mansion since the 1850s © Andrew Shiva

A pair of large Assyrian relief sculptures, similar to those recently destroyed by Islamic extremists in Iraq, has been quietly removed from an historic mansion in Scotland and sold abroad for £8m, despite concerns that they were part of Scotland’s heritage. The sellers were Newbattle Abbey College and the 13th Marquess of Lothian, better known as Michael Ancram, a Conservative peer and former party chairman.

Dating from BC860, the reliefs were stripped of Victorian overpaint shortly before the sale. John Curtis, the British Museum’s former keeper of the Middle East, says the removal of the paint is a “shocking and a tragic loss”. He says that “in the stripping process vestiges of original Assyrian paint may have been removed”. Curtis also privately advised that the reliefs were fixtures and he felt they should not have been taken out of Newbattle Abbey.

Last November the reliefs were quietly exported from the UK. They are likely to go to a private collector or possibly to a museum in the Gulf, such as Louvre Abu Dhabi or the country’s planned Zayed National Museum.

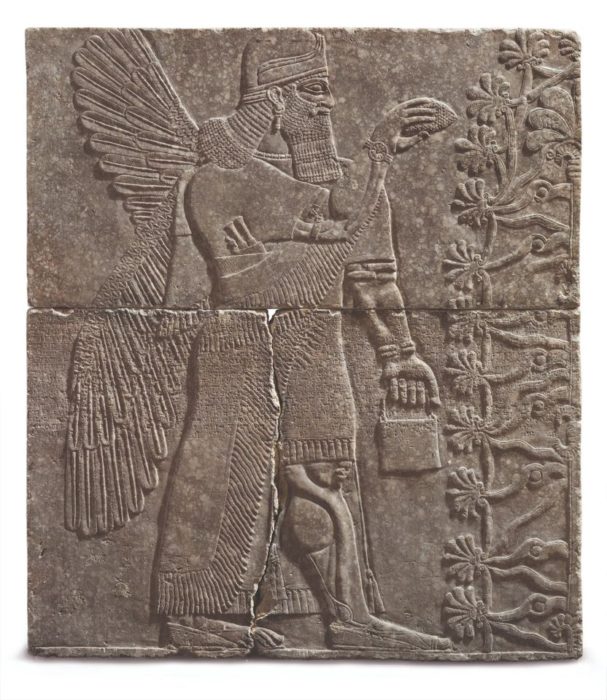

The pair of reliefs, depicting winged protective deities, were set in the walls of the palace of Ashurnasirpal II at Nimrud, in present-day northern Iraq. Nearly one metre high, they are carved from gypsum alabaster.

The panels were excavated by Austen Layard and were acquired in Baghdad in 1856 by the 9th Marquess of Lothian. He installed them in Newbattle Abbey, his 16th-century mansion in Dalkeith, ten miles southeast of Edinburgh. Some years later they were painted, to reflect how Victorian archaeologists believed they would have originally been decorated. They were then framed and set into the walls at the entrance to the mansion’s crypt.

The large Assyrian relief sculptures from Newbattle Abbey in Scotland © Dr J Stewart Stirling; Groves-Raines Architects

In 1937, the 11th Marquess gave Newbattle Abbey to the Scottish nation, for use as an adult education college. At that time the reliefs were apparently considered to be modern replicas and for the rest of the 20th century they remained virtually unknown to Assyriologists.

It was not until 2005, when Curtis inspected the reliefs and authenticated them, that their true significance became clear. By this time the family of the Marquess and the college had just begun discussing a possible sale with the London dealer Oliver Forge.

It was unclear whether the reliefs affixed to the wall were the property of the marquess or the college, which needed funds to maintain the building. A private arrangement was therefore made to split any proceeds, with around two-thirds ultimately going to Ancram’s family.

Another hurdle was to get permission to remove the reliefs, which were affixed to a wall in a listed building. Midlothian Council initially permitted them to be temporarily removed and it later allowed permanent removal, as long they were replaced with replicas. Although Historic Scotland was consulted, advice was not sought from National Museums Scotland.

Christie’s, which had been brought in to help find a buyer, advised that it would be easier to sell the reliefs with the Victorian overpaint removed. The panels were then sent to a London restorer. Although the stripping was done with care, Assyriologists believe that traces of ancient paint were lost. Last September the stripped panels were examined by specialists, who discovered traces of ancient Egyptian Blue pigment around the eyes.

This Assyrian relief of a winged deity sold for $31m at Christie’s New York in October 2018 © Christie’s Images Ltd 2018

In 2015, a year after the stripping, the marquess and the college decided on a change of approach, dropping Christie’s and entrusting the panels to Sotheby’s for a private sale. Although the reliefs were valued for insurance purposes at £32m in 2016, a sale at £8m was finally concluded last June. It is believed that they were bought by a European dealer, for onward resale.

Last October, Christie’s offered a finer and larger relief of a winged deity from the very same palace in Nimrud. With an unpublished estimate of $10m, it sold for $31m at a New York auction. The Iraqi government tried to block the sale on the grounds that the relief had been looted, but this failed since the Layard excavations and removals appear to have been authorised by the Ottoman sultan.

Following the Newbattle sale, the European dealer applied for a UK export licence. This was opposed by the Export Reviewing Committee’s expert, Margaret Maitland, the senior curator for the ancient Mediterranean collection at National Museums Scotland. She argued that the reliefs fell under the so-called Waverley criteria and an export licence should be deferred, to allow a UK buyer to match the price.

Maitland said that the reliefs were linked with British history, since they were part of an important decorative scheme in Newbattle Abbey. On aesthetic grounds, the carving is “exquisite”. “The reliefs of the Northwest Palace of Nimrud have been described by art historians as ‘magnificent’, ‘splendid’, ‘elegant’,” she said. “Designed to inspire awe, these panels are no exception.”

With regard to further research, if there were surviving traces of ancient paint, “this would be of great importance to the scientific study of ancient pigments and reconstructing the original colour scheme of the [Nimrud] palace”.

But when the committee met last October it unanimously voted against the advice of its expert, deciding that the reliefs did not fall under the Waverley criteria. The committee noted that there were numerous other Assyrian reliefs in UK museums. Although the reliefs were part of a significant Neo-Assyrian decorative aesthetic, “their removal from Newbattle Abbey, and subsequent cleaning, had substantially lessened their significance”.

This committee’s advice was accepted by the arts minister, Michael Ellis, and an export licence was then granted. It is assumed the reliefs went to Europe in November. Neither the marquess nor the college responded to enquiries from The Art Newspaper.

From Assyrian palace to Scottish mansion

Around 860BC The two reliefs are installed in room L of the Northwest Palace of Ashurnasirpal II in Nimrud

710BC The palace is abandoned and over the centuries is gradually covered by sand

1845-51 Excavation of the palace by Austen Layard

1856 Two reliefs (sawn from larger panels) are acquired by Lord Kerr, later 9th marquess of Lothian, who was then a diplomatic attaché in the British Residency in Baghdad; he brings them to Newbattle Abbey in Dalkeith

1878 Rebuilding work leads to the reliefs being painted and displayed in frames flanking a fireplace leading to the crypt

1937 11th marquess of Lothian gives Newbattle to the Scottish people to create an adult education college

2004 London antiquities dealer Oliver Forge begins private discussions on a possible sale of the reliefs

2005 Authenticity is confirmed by John Curtis of the British Museum

2006 Midlothian Council allows temporary removal of the reliefs. They are stored at National Museums Scotland until 2007.

2010 Scholarly article on the reliefs published by Julian Reade in the journal of the British Institute for the Study of Iraq

2012 Midlothian Council allows their permanent removal, on condition they are replaced by replicas

2014 Replicas made by Scottish company Relicarte. Christie’s becomes involved in a possible sale. Reliefs are stripped of Victorian paint by a London restorer

2015 On 5 March Islamic extremists bulldoze and destroy the Nimrud palace and the reliefs which had remained in situ. The Newbattle reliefs are delivered to Sotheby’s

2016 Reliefs valued at £32m for insurance purposes

2018 In June Sotheby’s completes a private sale at £8m. Pigment tests conducted on the stripped panels in September. On 17 October UK Export Reviewing Committee decides against recommending a deferral. In November the Newbattle reliefs are exported to a European dealer

Read original article here