Source:euronews.travel

Why preserving Iraq’s cultural heritage is crucial post-ISIS

The mountains of Iraq – Copyright CanvaBy Hannah McCarthy • Updated: 20/08/2021

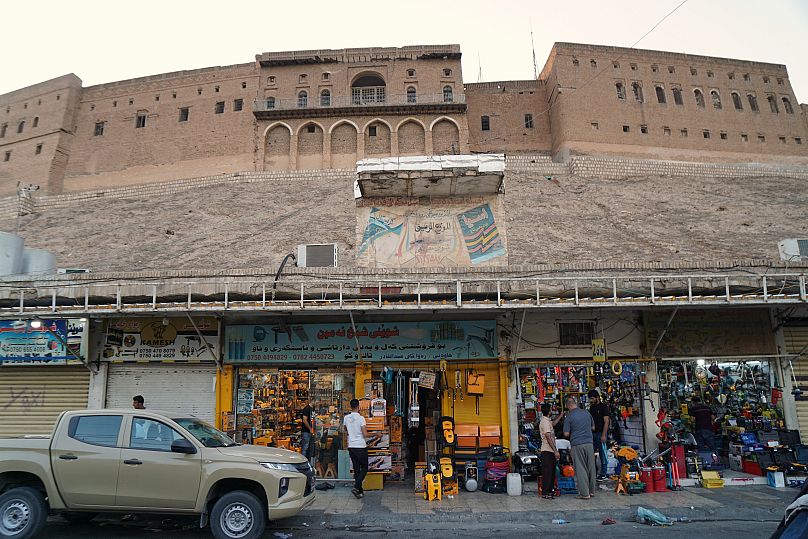

The Citadel in Erbil, the capital of the Kurdistan region in Iraq, received its UNESCO world heritage status in 2014.

That was the same year that the so-called Islamic State began its onslaught through Northern Iraq and seized control of Mosul city which lies just 80 kilometres from Erbil.

ISIS waged a campaign of “cultural cleansing, cultural eradication and cultural looting,” says Irina Bokova, the former head of UNESCO in Iraq. The destruction of religious sites and historic artefacts were an integral part of ISIS propaganda.

The deliberate destruction of Iraq’s cultural heritage was denounced as a war crime by UNESCO.

The terror group released online videos of ISIS militants destroying museum collections with sledgehammers and levelling Christian and Shia Muslim shrines in Iraq and Syria with dynamite.

Similar tactics were deployed by the Taliban in 2001 when they blew up two Buddha statues at the Bamiyan Valley, one of Afghanistan’s two UNESCO World Heritage sites.about:blank

The deliberate destruction of Iraq’s cultural heritage was denounced as a war crime by UNESCO (which now fears that it may see similar destruction in Afghanistan as the Taliban once again takes control).

“There is no doubt that ISIS represents one of the darkest moments in the history of Iraqi heritage and civilisation,” says Professor Abdullah Khorsheed Qader, the Director of the Iraqi Institute for Conservation of Antiquities and Heritage.

“More than 4,000 archaeological and heritage sites were under occupation in the provinces of Nineveh, Salahuddin, Anbar and Kirkuk.”

As videos circulated online of ISIS’s campaign of destruction, many in Erbil feared what could happen to the Citadel if it fell into the hands of ISIS.

The significance of the Citadel

“The Erbil Citadel has both archaeological and architectural significance,” says Alessandra Peruzzetto, an archaeologist specialising in the Middle East who works with the World Monuments Fund.

The fortress is surrounded by an Ottoman-era wall and lies in the centre of the city, on top of a hill that has grown through civilisations living and building on top of the ruins of their predecessors.

Kurds, Arabs, Turkmen, Muslims, Christians and Jews have all called the Citadel home and it is thought to be one of the longest continuously inhabited sites in the world, with roots stretching back 6,000 years. In an earlier iteration, it was the Assyrian town of Arbela and it also served as the backdrop for the battle between Alexander the Great and the Persian king Darius III.

Decades of neglect and underfunding

Even before the threat of ISIS loomed, the site faced an uphill battle for preservation. Decades of civil unrest, war and sanctions had meant that many of the buildings in the Citadel lacked electricity and proper drainage and sanitation systems.

While the central location of the Citadel meant the public could enjoy the site it also left it vulnerable to damage and pollution. Local authorities in the city even went as far as to demolish traditional houses to create a road for cars to drive directly through the Citadel in the 1960s.

As part of the process for bidding for UNESCO status, the commission installed a buffer zone and building regulations in the lower town to better protect the site.

The Citadel today

Fortunately, and to the relief of many, Erbil never fell to ISIS and the Citadel avoided the fate of other sites like Al-Nouri Mosque in Mosul or Hatra, another UNESCO site in Iraq.

The devastation left by ISIS in the rest of Iraq has prompted a renewed impetus to preserve and develop the Citadel. The site is now used to train other cultural staff in Iraq about conservation techniques and the management of historic monuments.

The site is now used to train other cultural staff in Iraq about conservation techniques and the management of historic monuments.

“We believe that the Citadel is the basis for building tourism in the Kurdistan region,” says Prof. Qader. “The site is being transformed from a semi-neglected archaeological site into a tourist site, similar to what Turkey has created with the Ankara Castle.”

The south-facing gate of the Citadel was recently restored by the High Commission for the Erbil Citadel Revitalization (HCECR). It was built in the 1860s but had been demolished and replaced in 1979 during Saddam Hussein’s reign.

The gate installed under Saddam distorted the Citadel’s heritage says Prof. Qader.

“It used Assyrian and Babylonian styles that were not in keeping with the true history of the site.”

The Citadel now includes the Kurdish Textile Museum, which displays some of the region’s carpet designs and fabrics, and a renovated Shihab Chalabi house, which houses the Iraqi branch of the French Institute of the Middle East.

After touring the Citadel, visitors can wander around the square in front which has plenty of restaurants and places to sit. In the evening there is a carnival atmosphere as locals gather around the Citadel for sunset.

- The 22-year-old British student who flew to Kabul has been evacuated from Afghanistan to Dubai

- Refugees in Iraq use the power of radio to tell their stories

- What’s it really like being a tourist in North Korea?

Across from the Citadel, visitors can also find some shelter from the sun and pick up a souvenir at the Grand Bazaar. Dating from the 13th century AD, the beautiful enclosed market is full of winding alleyways and arches displaying everything and anything a shopper can think of. Kurdish hospitality will be on full display as stall owners offer traditional tea and coffee to anyone who peruses their wares.

The scenes inside and around the Citadel could, however, look very different today had ISIS reached it.

The Old City in Mosul is a stark reminder of what could have happened to Erbil (and what could now happen in Afghanistan).

The Old City in Mosul is a stark reminder of what could have happened to Erbil (and what could now happen in Afghanistan). The historic city once served as a melting pot for different cultures and religions, where 19th-century churches stood around the corner from a 12th-century mosque. Today, four years after its liberation from ISIS, it remains mostly in ruins, with few remaining members of its religious minorities.

As Afghanistan now faces an uncertain future under the Taliban, we can only hope that the senseless destruction in Iraq serves as a warning about the need to safeguard Afghan heritage.