Iraqi and American archaeologists are digging at one of the world’s oldest urban centers—and finding evidence of the earliest long-distance commerce.

UR, IRAQThe bleak and tawny desert of southern Iraq is a strange place to find dark tropical wood. Even stranger, this sliver of ebony—no longer than a little finger—came from distant India 4,000 years ago.

Archaeologists recently found the small artifact deep in a trench among the ruins of what was the world’s first great cosmopolitan city, providing a rare glimpse into an era that marked the start of the global economy.

Ur- World’s first great cosmopolitan city

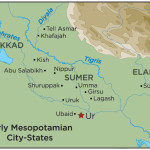

Mentioned in the Bible as the hometown of Abraham, Ur around 2000 B.C. was the center of a wealthy empire that drew traders from as far away as the Mediterranean Sea, 750 miles to the west, and the Indus civilization—called Meluhha by ancient Iraqis—some 1,500 miles to the east.

“There are texts that speak about the ‘black wood of Meluhha,’” saidElizabeth Stone of the State University of New York at Stony Brook, who is co-leading the Ur excavations. “But this is our first physical evidence.”

In the 1920s and 1930s, British archaeologist Leonard Woolley dug up some 35,000 artifacts from Ur, including the spectacular remains of a royal cemetery that included more than 2,000 burials and a stunning array of gold helmets, crowns, and jewelry that date to about 2600 B.C. At the time, the discovery rivaled that of King Tut’s tomb in Egypt.

But Ur and most of southern Iraq has been off limits to most archaeologists during the past half-century of war, invasion, and civil strife. A joint U.S.-Iraqi team reopened excavations there last fall, digging at the site for ten weeks.

But Ur and most of southern Iraq has been off limits to most archaeologists during the past half-century of war, invasion, and civil strife. A joint U.S.-Iraqi team reopened excavations there last fall, digging at the site for ten weeks.

Unlike earlier generations, today’s archaeologists are less interested in breathtaking gold objects than in clues like the bit of ebony that will help them understand more fully this critical time in human history.

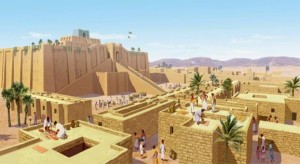

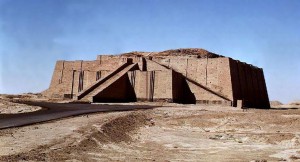

Although now situated on a flat and dry plain, Ur once was a bustling port on the Euphrates River laced with canals and filled with merchant ships, warehouses, and weaving factories. A massive stepped pyramid, or ziggurat, rose above the city and still dominates the landscape today.

Ur emerged as a settlement more than 6,000 years ago and grew to prominence in the Early Bronze Age that began about a thousand years later. Some of the earliest known writing—called cuneiform—has been uncovered at Ur, including seals that mention the city.

But the real heyday came around 2000 B.C., when Ur dominated southern Mesopotamia after the fall of the Akkadian Empire. The sprawling city was home to more than 60,000 people, and included quarters for foreigners as well as large factories producing wool clothes and carpets exported abroad. Traders from India and the Persian Gulf crowded the busy wharves, and caravans arrived regularly from what is now northern Iraq and Turkey.