Iraq’s Cultural History on the Auction Block

Marie-Helene Carleton and Micah Garen

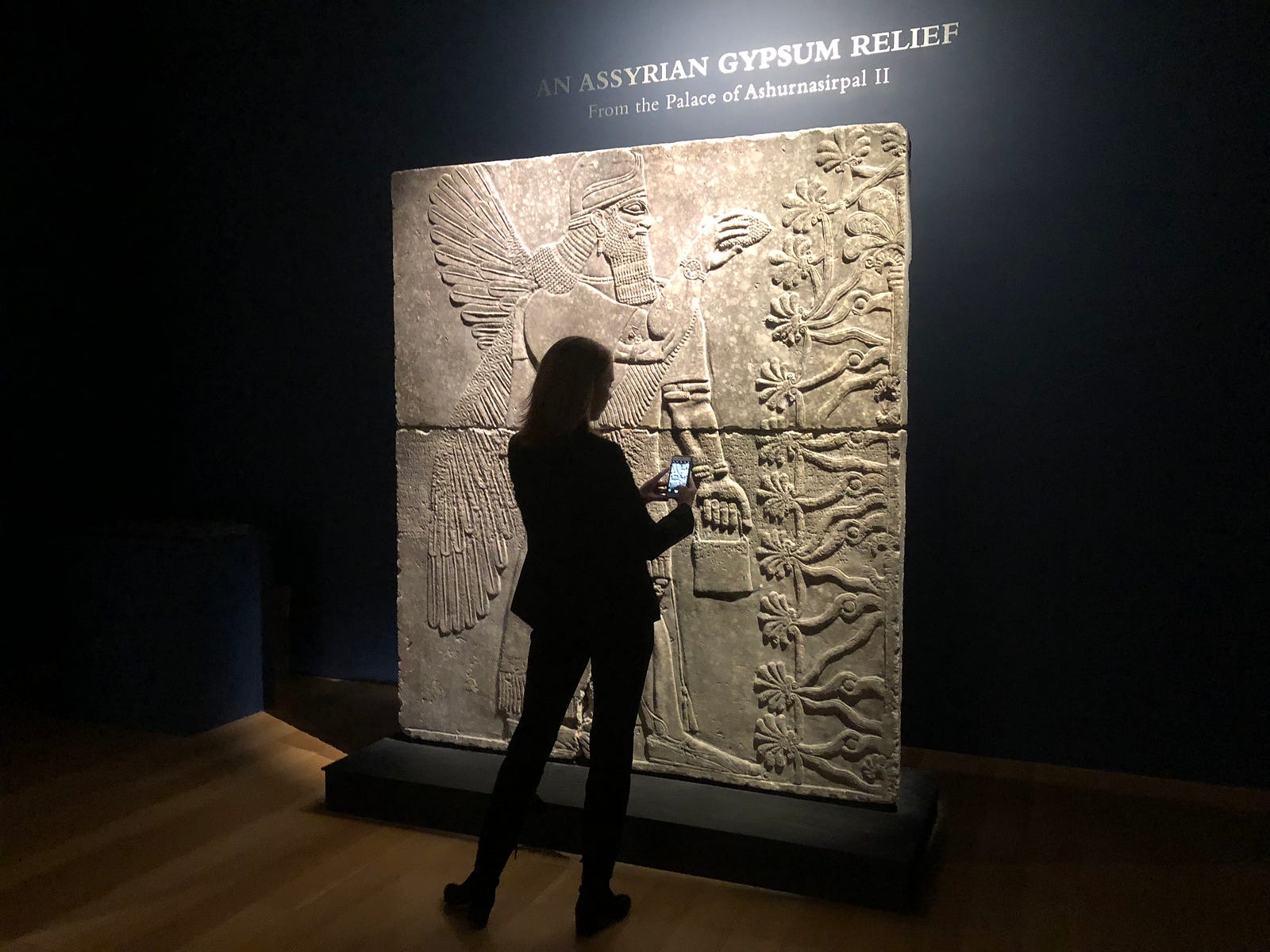

Christie’s, the auction house in New York, is poised to sell an artifact called “An Assyrian Gypsum Relief of a Winged Genius” from the famed Iraqi archaeological site of Nimrud. A Christie’s spokesperson conservatively estimated the artifact would sell for at least $10 million. An expert in the art of the ancient Middle East who preferred not to be named because of the amounts involved in this sale, stated he wouldn’t be surprised if the auction topped $20 million, which would exceed the current record for an Assyrian relief sold by Christie’s London in 1994.

This relief from the famed palace complex of King Ashurnasirpal II excavated by British archaeologist Sir Austen Henry Layard in the 1840s, is described by Max G. Bernheimer, Christie’s International Department head of Antiquities as “without question the most exquisite to come to the market in more than a generation.”

The relief arrived in the US in 1859 as a gift from an American missionary Dr. Henri Haskell to his friend, a professor at the Virginia Theological Seminary. At the time, such depictions were thought to have biblical significance and to inspire young seminarians in their missionary work.

In addition to what experts call its “impeccable provenance”, an unspoken aspect of the relief’s value arises from its now increased scarcity. Nimrud, the Assyrian archaeological site in northern Iraq that, until a few years ago, still contained about 100 reliefs in the remains of the ancient palace, was completely destroyed by ISIS in late 2015. They went in with explosives and jackhammers, filming the destruction of what they consider the idolatry of the pre-Islamic world. The expert in ancient Middle Eastern art we spoke with stated that “the destruction of the kind of slabs that this one represents in close to 100 percent.”

The sale, eagerly anticipated by some, is being criticized by a group of Iraqi scholars and activists who value the relief as an irreplaceable part of Iraq’s cultural history. The looting of Iraq’s cultural history increased dramatically with the US-led war in Iraq starting in 2003, and rose to unprecedented levels recently in areas under the control of ISIS.

“ISIS is destroying Iraq’s heritage, and Christie’s is selling Iraq’s heritage,” says Abdulamir Hamdani, an Iraqi archaeologist who helped lead efforts to help protect archaeological sites from looting following the 2003 US-led invasion of Iraq. Mr. Hamdani is currently working in the Department of Archaeology at Durham University in the UK and helping train Iraqi archaeologists.

Mr. Hamdani’s concern is not only with the auctioning off of Iraqi history, but that the selling of Iraqi antiquities for high prices in the art market could create a demand for objects that would increase looting from archaeological sites.

Patty Gerstenblith, a law professor at DePaul University who focuses on cultural heritage law, shares his concern. “Sometimes when there are highly publicized high-end sales, it might encourage more looting, it’s possible,” she says. However, she believes the focus should not be stopping the sale of objects legally excavated before the UNESCO convention of1970, but rather on increasing efforts to prevent looting today.

The Assyrian relief for sale by Christie’s falls within the “long-standing and legitimate market for works of art from the ancient world” and the excavation had the permission of the Grand Vizier of the Ottoman Sultan, according to a statement by a Christie’s spokesperson.

Challenging the legality of excavations and expatriations conducted before the state of Iraq existed, and before the UNESCO Convention of 1970, would be problematic, and most Western scholars emphasize that cultural laws are not retroactive. According to the ancient Middle Eastern art expert, “If this sale wouldn’t stand a legal challenge, then 90 percent of antiquities everywhere wouldn’t stand a legal challenge.”

Iraqi archaeologists and activists, however, say the sale is as much an ethical question as a legal one. They challenge the existing paradigm in which Western institutions and Western art markets continue to control a large portion of their cultural history with over 60 museums around the world housing artifacts from Nimrud. And although Christie’s publicly denies that the destruction of Nimrud by ISIS has increased the value of the relief, it is clear that there is now a very limited supply of legitimate artifacts from Nimrud. When reached by phone, a Christie’s sales associate stated that the destruction of Nimrud was a reason for the high value of the relief. “It’s part of what makes it such a special piece because we don’t think there are any more left at the palace.”

The Virginia Theological Seminary declined to respond when asked about the ethical implications of auctioning off this piece of Iraq’s history, saying simply that all questions should be directed to Christie’s. The seminary has stated in a press release that they could no longer afford the insurance on the relief and that proceeds from the auction will go towards a scholarship fund.

Jabbar Jafaar, an Iraqi cultural activist based in the US with the non-profit Voices for Iraq, has started an online campaign calling for a halt to the sale. He believes that the relief is part of Iraq’s patrimony “and should be returned to Iraq.”

Read original at https://medium.com/@FourCM/iraqs-cultural-history-on-the-auction-block-a1ebddf37764